You see it every day. Graffiti, whether lettering or images, is everywhere: fences, overpasses, structures, train cars. What’s the big deal? To the law-abiding taxpayer, money is the big deal: $12 billion in clean-up alone1 annually across the United States. That figure doesn’t include loss of revenue; public transportation and businesses suffer when patrons and tourists avoid these areas due to a sense that the area is not well-policed, dangerous, or run down. Not to mention that property values drop as much as 15% due to concerns about gang activity and the perception of decay and economic decline – far from a “victimless” crime!

Is eradication of graffiti a losing battle? Not by a long shot. Studies show that removal within 24 to 48 hours results in a nearly zero rate of reoccurrence2. Many cities and communities enforce strict graffiti removal policies that discourage not only the artist, but copycats from adding their own tags in the territory as well.

Enter technology: there are two different categories of coatings that either facilitate the removal of graffiti or repel graffiti altogether. Sacrificial coatings are applied to a surface and then removed when graffiti is removed, often eroding away after a few cleanings. The other type of coating, often referred to as “anti-graffiti” or “graffiti resistant,” is permanent and is intended to be resistant to application of graffiti marking by preventing spray paint or marker from adhering to a surface in the first place, or to provide a surface from which such markings can be easily removed. This article will discuss the types of coatings and how to effectively evaluate them for cleanability, recoatability, and overall resistance to graffiti and the associated standardized test methods.

Sacrificial coatings

Most sacrificial coatings consist of one or two coats that form a colorless barrier over the wall or surface being protected. If the surface is vandalized, high-pressure water jetting (pressure washing) is often the remedy of choice, sacrificing a thin layer of coating with it. The system requires maintenance in that the coating must be reapplied after repeated washing. Sacrificial coatings are typically comprised of relatively inexpensive polymers such as acrylates, biopolymers, and waxes. These polymers often have low cohesive strength and are typically weakly bonded to the substrate to allow for easy removal.

Permanent coatings

Permanent coatings are often more expensive than sacrificial coatings but can be a good investment since the need for re-application is all but eliminated. These coatings create a protective surface that prevents graffiti from bonding to it. If graffiti application (considered vandalism) takes place, these markings can be removed with solvent, detergent, water, or even hand-wiping with a rag. The underlying surface and the protective coating remain intact.

Types of permanent coatings include polyurethanes, nano-particles, ceramics, fluorinated hydrocarbons, silicones, and siloxanes. The high crosslink density of these coatings results in a less porous surface and reduces the ability of the graffiti to adhere to the slick finish. Fluorinated coatings can be very effective because of their electronegativity; they show very little affinity for the electrons of other elements. Permanent coatings operate on the premise that surface energy is decreased at the interface, similar to how a Teflon coating behaves. These coatings also have the added benefits of being chemically inert, very durable, and often hydrophobic. The drawbacks are that they are often expensive and can be difficult to apply.

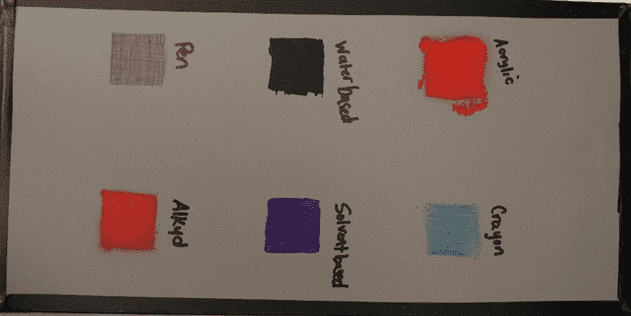

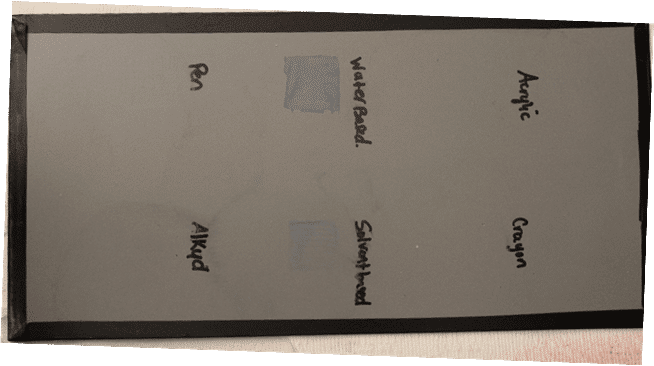

Evaluating Graffiti Resistance: ASTM D6578 (Cleaning by hand wiping using solvents)

ASTM D6578 is a standard practice intended to evaluate the efficacy of the permanent classification of anti-graffiti coatings, although it could be used for sacrificial coatings as well. Test panels of any applicable substrate material (preferably smooth) are coated with the coating under evaluation. Six graffiti marking materials (solvent-based permanent marker, acrylic and alkyd spray paints, wax crayon, ballpoint ink pen, and water-based marker) as well as any other applicable staining materials are applied to the coated surface in 1-inch square areas (see Figure 2 below). After a curing period of the graffiti markings is allowed, typically 24 hours, the removal of the markings is attempted beginning with a dry cloth, then through a series of increasingly stronger liquids (mild detergent, isopropyl alcohol, mineral spirits, xylene, and lastly methyl ethyl ketone) until one is found to completely remove the markings (see Figure 3 below). The Cleanability scale ranges from 1 to 10, with a 10 indicating that the marking was completely removed with the dry rag, and 1 indicating that the marking was not cleanable with any of the liquids. Each marking material is rated separately; for example, the water-based marker could be rated a 9 (cleanable with detergent), while black alkyd spray paint could be rated a 6 (cleanable with xylene).

Cleanability is assessed either visually with the unaided eye, or instrumentally by measuring color and gloss change of the marked area before marking and again after cleaning. There is also an optional recleanability procedure in which the same area is re-marked with the same material and the cleanability assessment is repeated until the marking is no longer cleanable.

This test method also includes methods for natural (outdoor) weathering and laboratory accelerated weathering using either a fluorescent-UV or Xenon arc apparatus. The coating under test can either be subjected to weathering before or after the graffiti markings are applied.

The benefits of this procedure is that the rating system is easy to follow, any marking materials can be used, and any applicable substrate can be used. The drawbacks are that it is very labor intensive; all cleaning is performed by hand wiping, and no hot water is used. It should be noted that the results are not intended to correlate to rough surfaces.

Evaluating Graffiti Resistance: ASTM D7098 (Cleaning using pressure-washing)

ASTM D7098 is a standard practice that is much more geared toward building materials in that the substrate materials are specified therein: concrete, masonry, and natural stone (see Figures 5 and 6 below). Additionally, the cleaning methods employed are more consistent with those used in commercial building cleaning.

The marking materials employed are spray paint and solvent based ink markers, both in black, red, and blue. The markings are applied in parallel lines as opposed to the 1-inch squares of ASTM D6578 (see Figure 7 below), and then are allowed to dry, typically for a 5-day period. The markings are then cleaned starting with the least aggressive power-washing method (high pressure, cold water wash); if any marking remains on the panel, the next most aggressive method is employed (a commercial graffiti cleaner with high pressure, cold water wash). If the markings are still not removed, a high pressure, hot water (140 to 180°F) wash is employed, finishing with the most aggressive method (sodium bicarbonate pressure wash). See Figure 8 for an example of the test sample following a cleanability method. If the markings are completely removed with one of these methods, the coating is rated as Cleanability 1 through 4, respectively. The specimens are cleaned at a distance of 10 inches at a pressure of 800 to 1500 psi. The percent of marking material remaining is reported.

The test procedure also employs a recleanability procedure, which consists of repeating the above procedure until the markings can no longer be removed. Therefore, this test method is more intended for permanent coatings rather than sacrificial coatings.

The benefits of this procedure are that the substrates consist of common building materials as well as cleaning methods that are typically employed in commercial building cleaning.

A drawback to both methods is that neither includes a procedure to evaluate the recoatability of permanent or sacrificial coatings, which would certainly be of importance if the life expectancy of the structure is long-lasting. Recoatability should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis because the life expectancy of the entire coating system will be an important factor; the service environment and the point at which the coating system would be slated for complete removal and replacement will both influence the parameters of the evaluation. The primary function of the coating system, whether it is corrosion protection or aesthetics, as well as the overall cost of the coating system will also play important roles in determining whether recoating is a more economic option than removal and replacement.

CONCLUSION

The true cost of graffiti to a property or business owner is difficult to calculate because factors such as lost revenue, reduction in tourism, or decrease in property value cannot be precisely determined. The cost of graffiti removal itself is staggering, however prompt removal is a successful deterrent from recurrence. Creating a surface that does not allow adherence of the markings or facilitates ease of cleaning of the markings is a successful strategy in limiting or eliminating graffiti altogether. Test methods are available to evaluate the effectiveness of permanent and sacrificial anti-graffiti coatings. The specific method should be chosen based on the intended substrate and the preferred cleaning method that will be used in practice.

1 https://artradarjournal.com/2021/11/17/what-does-seattle-pay-to-clean-up-graffiti-a-year/

2 https://www.gwinnettcb.org/resources/facts-figures/graffiti-facts-figures/

About the Authors

Written by Carly McGee & Dan Chasky

Co-Author, Carly McGee, is the Materials & Physical Testing Laboratory Manager for KTA-Tator, Inc. where she has been employed since 2001. Carly is an SSPC Certified Protective Coatings Specialist, a member of the Pittsburgh chapter of the American Concrete Institute (ACI), and ACI Certified Concrete Field Testing Technician Grade 1, a member of ASTM Committees G01 (Corrosion of Metals) and C09 (Concrete and Concrete Aggregates), and a Director for the Research Council on Structural Connections.

Co-Author, Dan Chasky, is a Project Manager/Coatings Application Specialist with KTA-Tator, Inc. He is an SSPC Level 1 Coatings Application Specialist with nearly 10 years of coating application experience.